Crumbling under society’s fire

Libyan norms equating cruelty and manliness confound the timid baker at the centre of this IPAF-winning debut.

By Marcia Lynx Qualey

How does a sensitive man’s life taste? What if he is pounded, shaped, and leavened with rigid expectations about masculinity, then baked at a temperature far higher than he can bear?

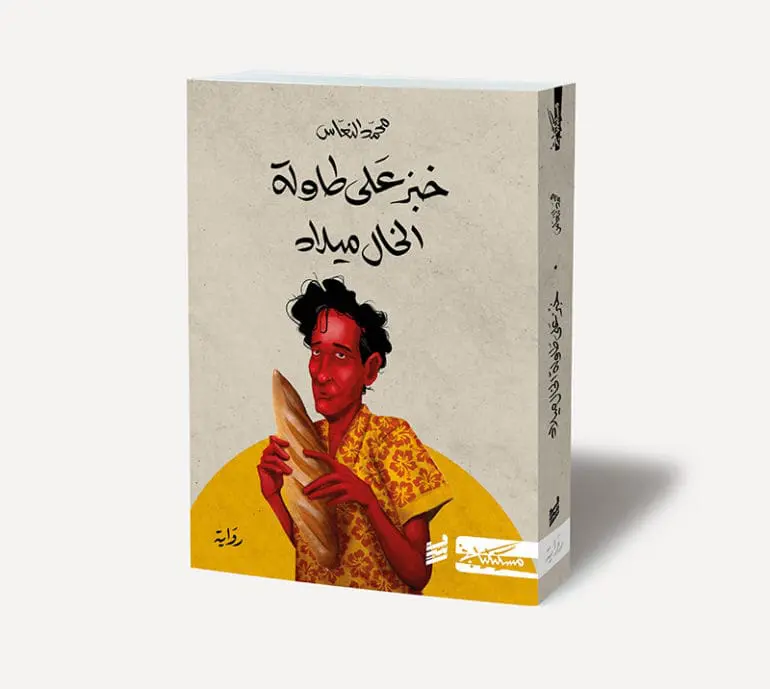

These questions animate Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table, a powerful, voice-driven novel by Libyan writer Mohammed Alnaas. In it, the protagonist gives the reader an extended baking lesson as he shows us around his house and tells us his never-quite-coming-of-age story.

The novel—Alnaas’s first—was winner of the 2022 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, making Alnaas the youngest author and first Libyan to win the $50,000 prize. The recognition is deserved: Alnaas keeps tight narrative control over multiple timelines as Milad relays his life story, swinging us up to the heights of gustatory pleasure and down to the horrors of being trampled by dozens of fellow army conscripts. Throughout, scenes of violence are tempered by a self-effacing, sometimes unwitting humour, as when Milad hangs himself from the living-room chandelier, then changes his mind, regretting what his wife will have to clean up.

Each of the book’s six chapters opens with a pointed statement about manliness in Libya. The first is: “A family and their Uncle Milad.” The epigraph goes on to explain that this is meant as a reproach to the man who has no authority over the women in his family. The novel suggests that our Milad might be the reason for the saying’s spread.

Milad tells us that he and his four beloved sisters grew up in and outside Tripoli, and that he was part of the generation that came of age in the 1980s. While he describes this as a time of economic crisis, Milad’s dreams were relatively small: to make bread in his father’s bakery. But Milad, who hates confrontation, loses the bakery to his opportunistic uncle. He still might have been content baking bread at home and caring for his hardworking wife, Zaynab. But Milad is easily swayed by others’ opinions. When his cousin Abdel Salaam tells him he’s a laughingstock because he can’t control the family’s women, this sets off a chain of events that leads to the novel’s ending.

The novel’s nearest ancestor is perhaps Ghada Samman’s 1998 short story ‘Beheading the Cat,’ also centred on a man faced with competing ideals of manhood. In Samman’s story, a ghostly voice tells the protagonist he must behead a cat in front of his bride on his wedding night, so that she understands the consequences of disobedience. Similarly, one of the anchoring proverbs in Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table translates loosely to “Smite the cat and school the bride.”

But if Samman’s narrator believes himself a dithering “Lebanese Hamlet,” Milad is more of a holy fool, and it is his tender naïveté that allows us to be shocked afresh by life’s familiar cruelties: by the way men are socialised in the military, how boys are taught not to complain, the corrosive nature of power.

Throughout the novel, cousin Abdel Salaam tries to school Milad in manhood. It is Abdel Salaam who informs Milad that his wife has been riding around in her boss’s car and that his niece is wearing jeans. Unfortunately for Milad, he doesn’t have a counter-thesis, another way of understanding the world. Whenever Milad takes a more feminist course of action, it’s not because he means to contest patriarchy—he just wants to avoid conflict. When he and Zaynab are on their honeymoon in Tunisia, he agrees she can wear a bikini because he doesn’t want a fight.

But like any wise fool, Milad also has his insights. He’s heard musicians sing about being madly in love, and he tells us that Libyan men will listen with such sensitivity that you’d think “they are the sweetest creatures in the universe.” But these same men will go on to abuse their wives and sisters. One can almost hear Milad shaking his head over the readers who will sympathise with him in the novel, and yet will bully a real-life Milad.

All the strands of the novel come together in the book’s powerful final scene. It’s a moment from which the reader can’t escape, as we are right there in the kitchen alongside Milad, poised to eat his bread. The reader thus becomes not only listener, but also accomplice. And as with the conclusion of other compelling literary portraits, the end makes the reader want to return to the beginning, both to remember how all this came about, and perhaps also hoping that, on a second reading, things might turn out differently.